The Big One

You’ve heard of the San Andreas Fault. Everyone has. The sinuous line that runs north and south along the entire vertical length of California, defining the collision zone where the Pacific Tectonic Plate (the earth’s largest) noses into the North American Plate. Scrunch. And — very important — those two magnificent plates also scrape along each other, with the Pacific Plate, including San Diego, dragging north, and the North American Plate, including San Francisco, dragging south. Screench.

In your children’ geology textbook — should your children have the good fortune to attend a school where they still teach geology — the fault appears as a narrow line, giving the impression that someone on the west side could hand a martini across to a pal on the east side.

Not so.

the slow motion calamity of colliding and sliding tectonic plates creates not a crisp line but a rumpled zone, in places miles wide. Hard to visualize but try this thought experiment. You hire a husky stevedore to pile up ten squares of corrugated cardboard and to stand an anvil atop the stack. Your pal hires a second stevedore to repeat the process. You invite them to slide their piles face to face. When the bell rings, each is to shove his pile forward with all his might, and the one on the right is to simultaneously cramp his heap south while the one on the left is to cramp his heap north. Promise generous cash rewards to the one who a.) advances forward the most and b.) the one who advances north or south the most. Clang! Go! At the half minute mark ring the bell again.

Watch the collision zone — the fault line — in between the first and second bells. There you will see not a precise line but a mangled mess of cardboard layers crumpled and mashed and disfigured in random ways. Some layers will deviate from horizontal to vertical. Some will fold over backwards upon themselves. Some will turn to mush. Some layers will slouch under the oncoming mass. Some will slop over. The force of your mini tectonic plates grinding past each other will shatter the surface layers such that subsidiary cracks appear on either side of the fracture zone.

An imperfect model you geologists might say. Fair enough, but you get the picture. And if you don’t, you can remedy that by coasting your bicycle down a two-lane country road just east of Palm Springs, California. That road happens to cross the San Andreas Fault Zone shortly before it dives under, and creates, the Gulf of California. Along the way you will witness mangled and contorted rock formations to excite your imagination, demonstrating as they do geologic forces beyond reckoning.

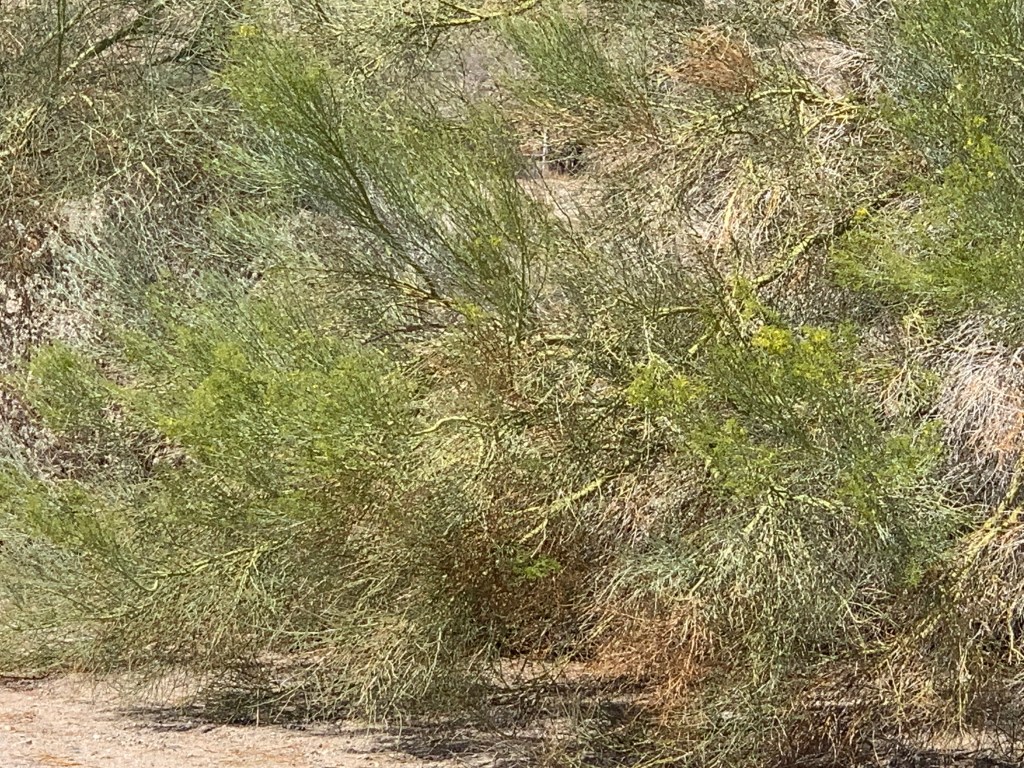

Also . . . desert flora testifying to just how resilient and adaptive Mother Nature can be, including my favorite, the Smoke Tree. Their appearance suggests that Dead Tree would be a better name, but, yes, if you see one in the distance and kind of squint your eyes, indeed it does sort of resemble a puff of smoke. The cacti and paloverde and smoke trees care not a whit about the next earthquake, but it will surely come. The fantastic distortions of the strata don’t result from slow creep, instead from the sudden jarring release of pressure now and then. The Big One.

Great explanation and photos!

LikeLike